Reckoning

The Grateful Dead and the discipline of the American West

December 29, 2025

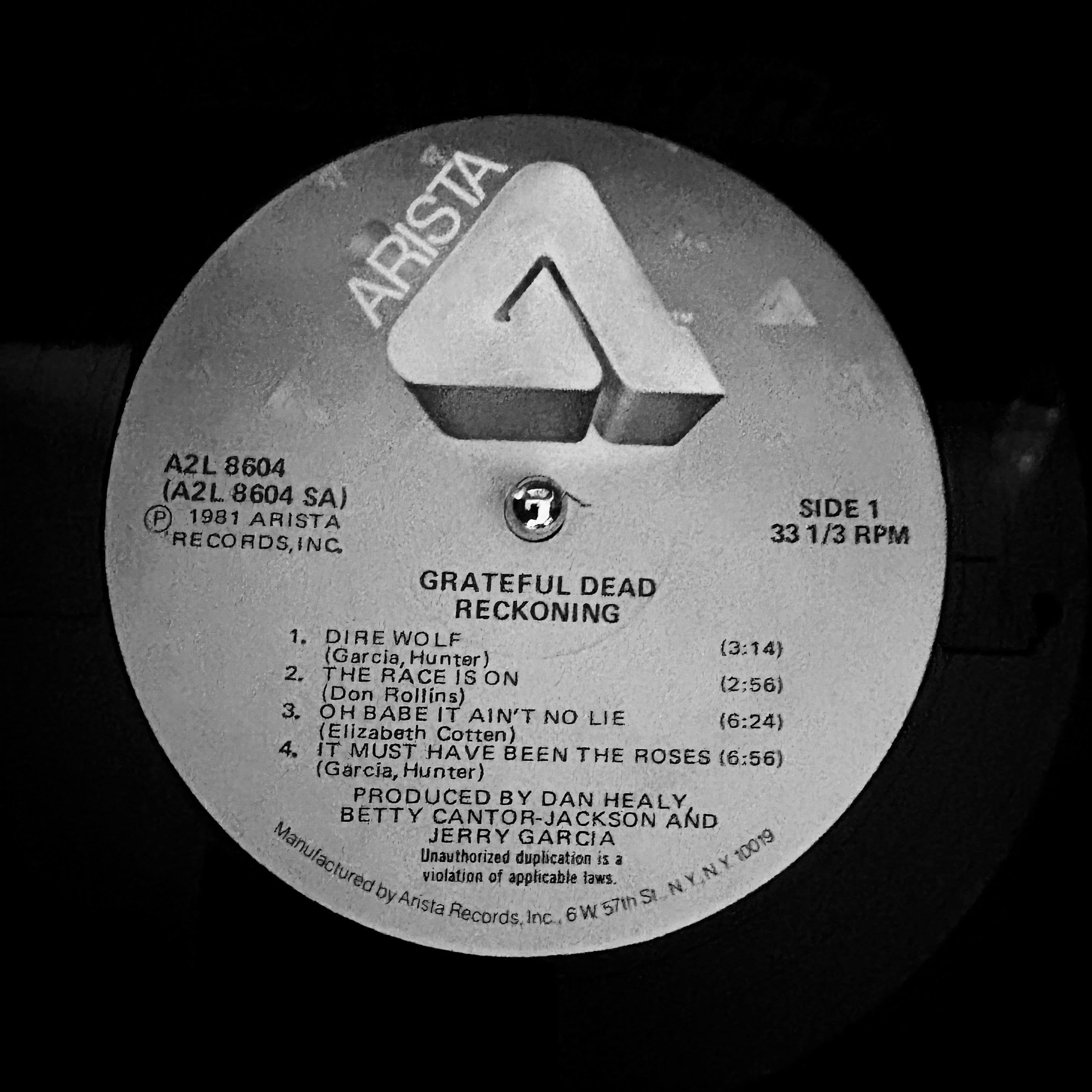

My earliest memories of music are tied to the album Reckoning by The Grateful Dead. I borrowed the CD from my dad sometime around 7th or 8th grade, mostly out of curiosity. I may have heard a friend mention the band or saw someone at school wearing a dancing bears t-shirt. Whatever the reason, it stuck.

Looking back, two songs stand out: "Dark Hollow" and "Been All Around This World." They're strange choices for a middle school kid from Michigan, but they stayed with me. I didn't think much about why at the time.

Growing up, my grandpa kept a wicker basket beside his favorite chair in the living room. Inside were golf magazines, bird dog magazines, and a stack of Louis L'Amour novels. Golf and bird dogs had their appeal, but it was the cowboys that stayed with me, lonesome figures riding beneath wide skies with a six-shooter on the hip and lever-action rifle in the scabbard. There was a sense of determination in those stories, and a promise of adventure beyond the horizon.

A few years later, when I first heard Reckoning by the Grateful Dead, that same feeling returned. The songs land squarely in the folk and country tradition, performed acoustically and stripped down to an intimacy most people don't associate with the band. It felt familiar in a way that I couldn't yet explain, as if the meaning arrived long before the understanding did.

The first song on Reckoning is “Dire Wolf,” a man sitting by a campfire with little more than a bottle of red whiskey for dinner and company. The album only moves deeper into that box canyon from there. “Been All Around This World” could score any Louis L’Amour novel, a final stand set in the Blue Ridge Mountains, a rifle slung over the shoulder.

The Grateful Dead have now been weaving their way through American culture for more than fifty years. When Dead & Company played their final run of shows in 2023, more than eight hundred thousand people attended twenty-eight concerts across nineteen cities, from New York to San Francisco.

The documentary Long Strange Trip (2017) surfaces some of what it took to keep the band moving as their audience grew. Each show required transporting an increasingly elaborate operation from one city to the next—semi-trucks, crew members, scaffolding, and a sound system that seemed to evolve with every tour stop.

By 1974, the setup had become the Wall of Sound, a custom system designed by Owsley "Bear" Stanley with more than five hundred speakers generating upwards of twenty-five thousand watts of power. Night after night, the crew assembled it piece by piece, tore it down after the show, and loaded it onto semi-trucks bound for the next city. However unwieldy the setup became, the routine stayed the same: get the system set up, play the show, get back on the road and do it again.

That brand of discipline didn't start on the road. For some members of the band, it was already familiar long before they stepped onstage.

For Bob Weir, that way of working was there from the beginning. Many of the musicians he admired most came from traditional country music. In an interview published in GQ, Weir recalled traveling to Nashville with Jerry Garcia, where they made a point of seeing performers like Porter Wagoner, George Jones, and Dolly Parton. "We didn't have chops like those guys," he said.

Weir grew up near San Francisco, but his encounters with western culture came as a child. His family spent summers in Squaw Valley, where he hung around the riding stables, learning from the men who ran it. One of the ranch hands, an old cowpoke with a glass eye named Bud, taught him how to cut cattle.

He wasn't alone in bringing that sensibility to the band.

One of the people who arrived with a similar background was John Perry Barlow. Barlow met Bob Weir as a teenager at Fountain Valley School in Colorado, a boarding school for troubled kids set against the open landscape of the Rockies.

Barlow grew up on a working ranch in Wyoming, where responsibility arrived early and stayed. When his father suffered a debilitating stroke years later, Barlow returned home to keep the operation afloat and remained there, managing the ranch for the next two decades. During that time, he sold film scripts and wrote lyrics for the Grateful Dead, helping to keep the ranch going. Songs like "Cassidy", "Hell in a Bucket", "Estimated Prophet", and "The Music Never Stops" carried the same sense of movement, labor, and consequence that shaped his life on the ranch.

When I sit down and listen to Reckoning now, I still hear it the same way as I did back then. The songs carry a quiet authority earned through hard work and repetition. No flash. No bravado.

The Grateful Dead have always been associated with freedom, but not the kind that comes easily. Reckoning shows how much discipline it took to hold onto it.

Further Reading

- Rick Griffin — Biography — Artwork from the album cover.

- Bob Weir Profile (GQ) — GQ profile of Bob Weir.